Jonathan Sampson, MD of automotive training specialists, AutoMate Training, looks at why vehicle steering is heading towards a ‘hands-off’ future.

For the best part of the automobile’s 130 year existence it’s the steering wheel that has been at the centre of the driver’s relationship with the car. But it’s the very subjective need to cater to the human element of that relationship that continues to cause headaches for engineers the industry over.

Quite simply, steering design has come to embody one of the great questions driving the automotive industry at the moment: just how much involvement and control are drivers willing to cede in the pursuit of a more efficient, more technological and, eventually, more autonomous future?

The answer is complicated, particularly when we consider that ever since engineers began envisioning systems to make the job of steering easier, people have questioned just how much these systems detract from the natural pleasure of actually driving a car.

Lightening the load

You have to go back as far as the Benz Patent Motorwagen to find the origins of the basic car steering system. In 1886, Karl Benz used a boat-like tiller arrangement connected to rudimentary rack and pinion system to control his three wheeled, one cylinder marvel – the vehicle that would kick-start the idea of the ‘car’ itself.

But we can thank a rather brilliant American engineer called Francis W. Davis for one of the first true revolutions in the development of steering systems. A mechanical engineering graduate, Davis was acutely aware of how difficult steering had become on cars by the early 1920s, so in 1926 he patented an open-valve hydraulic power steering system, inspired by hydraulic press tools in the engineering workshops he frequented.

The beauty of the Davis design was that it also accommodated the need for driver feedback. Davis realised that whilst his system could be made to completely eliminate kickback from road surface imperfections (or as he called it, ‘steering reversibility’), doing so would create an unnerving disconnect between the driver and the car.

So, rather ingeniously, his system allowed a predetermined maximum amount of road shock torque to filter through to the driver in the form of feedback. Whilst Davis struggled with the economic fallout of the Great Depression, and squabbles over patents, there’s no doubt his system was a success: it was first implemented in the 1951 Chrysler Imperial, and by 1956, more than two million cars in the US were fitted with his hydraulic power steering concept.

Taming the tuck

The steering story from that point becomes far more complex, yet the basic struggle to balance driver involvement, whilst innovating new engineering solutions, remains a constant. In fact, there have been numerous innovations in terms of automotive steering that have existed with the sole purpose of adding to the performance driving experience. Take the Porsche Weissach axle. Here was an example where suspension design played a major role in changing how it felt to steer a car, demonstrating just how closely aligned steering and suspension can be when it comes to automotive design.

Back in the 1970s, engineers at Porsche developed a nifty solution to a handling quirk that had become quite commonplace by that point: lift-off oversteer – the tendency for the rear of the car to ‘toe-out’ when power was suddenly reduced on turn-in to a corner. The remarkable Germans recognised that by introducing a new, pivoted linkage into the traditional semi-trailing arm rear suspension, they could reverse the direction of the axle’s travel under negative acceleration loads, ‘tucking-in’ the rear to balance the car. So successful was the Weissach axle that emerged on the 928 Coupe in 1979, that it created a template for similar ‘passive’ steering control of the rear wheels – a concept that features in the design of multi-link independent rear suspension systems to this day.

Bringing around the rear

One of the interesting precedents created by the Weissach axle was the idea that the rear wheels could play a part in steering the car. Four-wheel-steering is a concept that came and went in the 1980s and 1990s, but failed to truly capture a profitable slice of the Western automotive market at the time.

There were some advantages: turning the rear wheels in the opposite direction to the fronts at low speed increased manoeuvrability, and turning them subtly in the same direction at high speed gave greater stability. Honda pioneered the system on the 1989 Prelude coupe, using a mechanical connection to transmit front steering inputs to a small slider that moved the rear tie rods.

More sophisticated electronic control systems could soon be found on the market, but the increased cost and weight of having an extra steering box made the systems difficult to justify. Today, however, rear-wheel- steering is making something of a comeback. Once again, it’s Porsche at the forefront of this technical development. Its new Active Rear Steering system on the 911 and 918 Spyder eschews the clumsy secondary steering box in favour of an independent electric motor for each rear wheel, which drives a separate toe-link in and out. The result is a far lighter and quicker system that effectively reduces the wheelbase of the car, both in low speed driving and during high- speed cornering situations. The advent of 48V electronic architectures will certainly assist the further refinement of such designs.

Variable opinions

It’s at the front of the car where we’ve seen the greatest changes occurring in steering design. Designs that alter the level of hydraulic assistance according to the vehicle speed have been around for decades now, pioneered by Mercedes-Benz under the guise of ‘Parameter Steering’ for its behemoth 1991 S-Class. But one innovation that really caused shockwaves came in 2004, sparking furious debate amongst consumers and critics about just how much technology is too much when it comes to steering design.

For years, BMW’s hydraulic power steering was widely considered the best in the business, full of feel and perfectly tuned in terms of weight and linearity. But in the midst of its great technological push in the early 2000s, the company hedged its bets on a revolutionary Active Steering concept for its popular 5 Series model.

Using an electronically-driven planetary gear-set mounted on the steering column, Active Steering varied the rack ratio between 10:1 (for super-quick low speed steering) and 18:1 (for ultra-stability at autobahn speeds). Uniquely, Active Steering could also introduce mild counter-steering to augment the operation of the Dynamic Stability Control.

In theory, BMW’s Active Steering meant you almost never had to take your hands off the wheel, but there were some issues with just how ‘natural’ this set-up felt, particularly when the directness of the steering changed suddenly as speed was lost or gained quickly.

How the future feels

Indeed, much of the criticism levelled at BMW for the lifeless feel of its electronic Active Steering has also been directed towards other manufacturers as they’ve begun to replace conventional hydraulic power steering with more efficient electric set-ups.

Using a column-mounted electric motor, these systems remove the need for power- sapping hydraulic pumps and space-wasting fluid lines, subsequently allowing for efficiency gains of around 6%. For manufacturers under increasing pressure to find every opportunity to reduce the environmental footprint of their vehicles, electric-power steering is a no-brainer.

Even the Porsche 911, that bastion of steering purity, fell victim to the electric- steering revolution for its latest generation. It’s no surprise that the purists were up in arms at that one, particularly as even the best of these systems seem to isolate the driver further from the business of steering than ever before.

But there’s more to this big electric switch than the environment: the systems are also the gateway to the autonomous future. Electric steering is far more easily compatible with the technology that is pushing us towards vehicle autonomy, such as lane-keep assist and systems like Tesla’s Autopilot. With manufacturers installing forms of semi- autonomy in even their least expensive cars, it’s no surprise to find that upwards of 65% of all cars on the road now feature a form of electric power steering – and don’t expect that number to go down any time soon.

WANT BETTER TRAINING?

Start your FREE AutoMate trial today by logging on to:

www.automatetraining.com.

Steering the wire

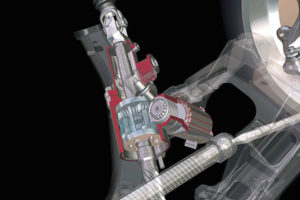

If foregoing clumsy hydraulics was the first step to streamlining our cars’ steering systems, then losing the mechanical connection between driver and wheels altogether was only a matter of time. Nissan- owned luxury manufacturer, Infiniti, has been the pioneer of something called ‘steer-by wire,’ a system that employs an electronically- controlled steering module to relay a digital signal to two electric motors mounted on the front axle, which then translate those signals into the movement of the front wheels.

Steer-by-wire has some unique advantages over a traditional mechanical connection: the electric steering motors can take commands directly from the electronic stability control system, as well as autonomous driving

technology, meaning the wheels can be turned independently of the steering wheel. The by-wire software can also automatically counter-steer to accurately compensate for road camber and crown and, on top of that, both the weighting and steering ratio can be adjusted infinitely.

Yet there are limitations. At this stage, Infiniti isn’t prepared to solely rely on a digital connection between the driver and the wheels, so a mechanical back-up linkage is retained, hence any weight advantage in the by-wire system is null and void.

But, for many, the real reason the system has struggled to find a market is because of what it does to the driver’s sense of actually driving. For the engineer, in theory, it’s a perfect system – by-wire steering removes 100% of kickback and completely insulates the driver from the imperfections in the road surface. And yet, most consumers still call for an element of that feedback to be retained as road feel, because anything less just feels unnatural and uninvolving.

So, 90 years after Francis W. Davis engineered-in a bit of road feel into his hydraulic system to please the driver, we’re still grappling with how to keep that very subjective connection between car and human alive. As we move towards a very inevitable autonomous future, the real question is how much longer will drivers need to even worry about steering at all?