Ben Johnson investigates another “classic” BMW with engine running woes.

Ah, the delightful symphony of an M70 engine’s running faults! It seems the universe has bestowed upon me a generous dose of these conundrums lately, as if my destiny is intertwined with the miseries of these engines. If you’ve been following my escapades, you’ll remember the 635 CSI from the previous issue, a real charmer of a headache. Well, brace yourself, because the latest episode in my automotive soap opera features the same M70 engine, but this time in a vehicle that can only be described as an avant-garde masterpiece of questionable modifications.

From the EML we managed to retrieve the following code – 1216: Throttle potentiometer

Picture this: a canvas of dirt brown Hammerite paint generously splattered across the engine bay, a truly artistic choice, if by “artistic” we mean a crime against aesthetics. But let’s not forget the throttle bodies, also graced by the same captivating hue – a colour that surely had da Vinci rolling in his grave. Of course, I jest…

E32 owners’ behaviour

Customers, those unpredictable creatures, can often succumb to the boredom-induced madness that leads them to commit vehicular atrocities. Yet, in our infinite wisdom, we must resist the urge to judge too harshly, for they are the benefactors of our livelihoods, they do, after all, pay our salaries.

Now, let’s talk about the peculiar habits of E32 owners. Either they, as the 635 owner does, look after and pamper their classics and no expense is considered too extravagant. Often these types will try to keep as much originality as possible – I love these types of customers. And then, I say as I take a very deep breath, there are those “other types”. It is they who have a tendency to shower their ageing steeds with ludicrous amounts of money, transforming them into rolling monuments of revolting extravagance. Massive alloy wheels, a fiberglass bonnet adorned with Japanese 90s style vents on a classic 7 series – yes, you read that correctly. But I digress; let’s not dwell on the eccentricities.

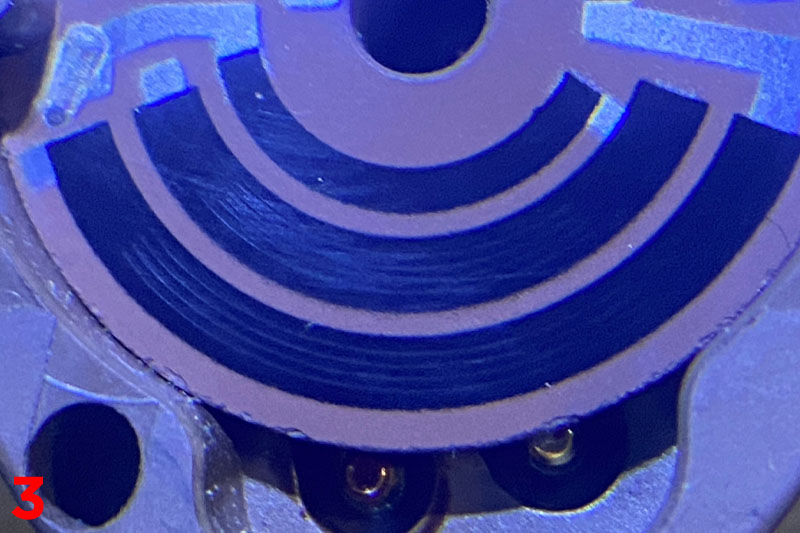

What baffles the mind, however, is the neglect of the engine’s vital components. While they splurge on the superficial, the heart of the beast is left to wither. Consider, if you will, the throttle body – a critical player in any engine bay. Inside resides a component with a penchant for drama itself, utilising those infamous sharp encoder wipers that gleefully carve into the resistive track on the circuit board encoder. It’s through this constant varying resistance that the EML (the forebear to the DME) deciphers the throttle’s every move.

Yet, as fate would have it, these systems have a flaw. The coating wears off, and suddenly, the resistance values embark on a tumultuous journey, resulting in a spectacle of erratic running that would make a circus seem orderly. BMW is not alone in this tragedy; even Maserati suffered a similar fate. Fear not Maserati owners, for a remedy exists – a hall sensor-based system, a beacon of hope for those plagued by throttle tribulations.

As for whether such a system can be retrofitted to the venerable M70 engines’ throttles, I remain in the dark, hopeful for a solution to emerge from the murky depths of automotive innovation. Wouldn’t it be a splendid twist in this tale of automotive woes? Only time will tell.

The initial step in this throttle-based odyssey was to seek out some data— specifically, resistance values that would grant both myself and my youthful accomplice, Erik, the ability to perform a simple yet illuminating comparison of the throttles in both their open and closed positions against a list of values. Astonishingly, BMW left us high and dry in the AIR platform as data was scarce to say the least when dealing with this vintage “classic”, leading us back to the reliable arms of our trusty friend, Google.

Cracking the vehicle

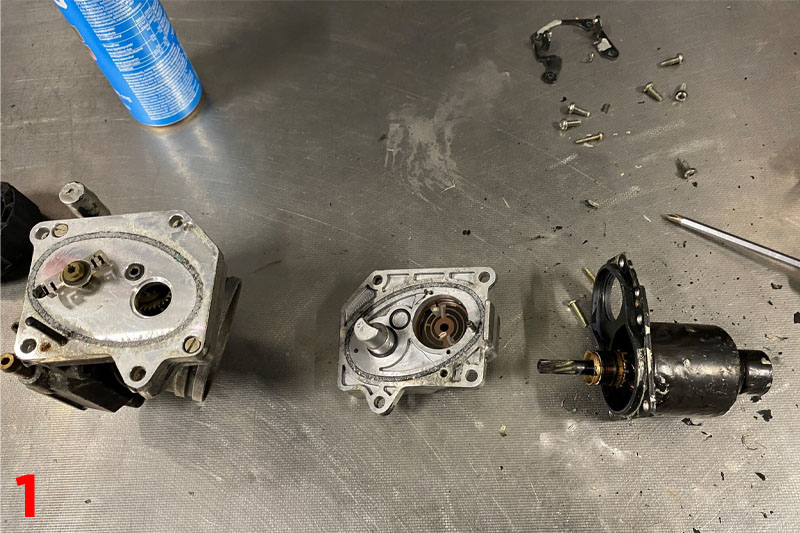

In the vast expanse of nonsense, spam and downright dodgy websites, we finally stumbled upon a trove of data that promptly pointed out the glaring issue: the throttle wiper was, in colloquial terms, thoroughly goosed. Armed with the determination to gather some hard evidence, we angrily chipped away the Hammerite coating from the throttle casing set screws, revealing the inner workings of this old school marvel. As the casing was split open, a surprise awaited us— the carbon brushes surrounding the motor collector were in pristine condition. Alas, the same could not be proclaimed for the state of the carbon track (Fig.1).

At first glance, it appeared passable, but armed with a magnifying lens and the piercing light of an LED, the true horror was laid bare—it was utterly and completely unserviceable – there would be no quick squirt of WD-40 to fix this. The intricacies revealed by this microscopic investigation painted a picture of wear and tear that escaped the naked eye, a tale of degradation that only magnification and illumination could uncover – and of course the fault finding with the KPS multimeter (Fig.2&3).

Swiftly armed with the diagnosis, I embarked on the quest to procure a pristine new throttle, a delightful component that came with a price tag of over 1,000 euros. Naturally, this revelation didn’t sit well with our resident car modifier, who, in a grand display of dissent, proclaimed, “I will source my own because that is far too much money.” My attempts at reason, akin to a lone voice in the wind, echoed with protestations such as, “the used one may be even worse. You are wasting time and money.” Alas, my words fell upon deaf ears, as the determined car modifier marched forth with his plan, heedless of my well-intentioned counsel. Such is the mind of the customer at times.

Replacing the throttle

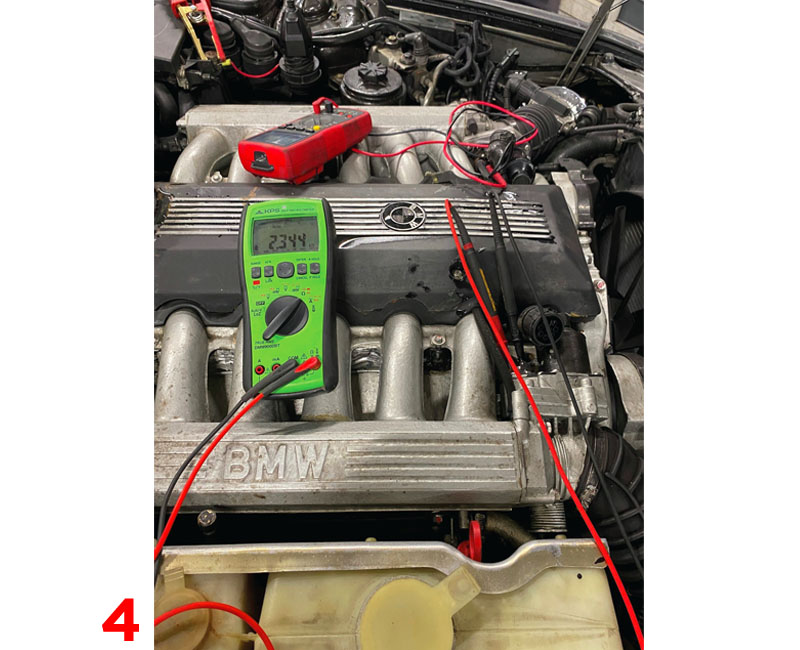

A week went by and the “new” throttle arrived. Erik wasted no time in popping it on to the right bank and in no time the engine was up and running again – this time, unsurprisingly, running even worse. Erik, being the young chap that he is, wanted to check the throttle with a resistance measurement, a request that I gladly fulfilled by grabbing my KPS meter from my faultfinding cupboard (Fig.4).

Sadly, as suspected, the “new” throttle was about as much use as a chocolate fireplace poker and it was swiftly taken off and plonked back where it belonged – the front desk. The intention was to call our customer and finally convince him that the only way this vehicle will get back on the road is if a properly working throttle is bought and fitted. For warranty reasons, we were unable to open the casing and inspect the donor throttle, but let’s be honest – the same sort of track faults will be present if anyone ever bothers to open it up.

How can I sum up this story? Well, if I had a pound each time that a customer dictated a diagnosis process, then I would be considerably richer than I am at present. As fault finders, we must constantly tread the fine balance of doing the job right and doing the job that the customer wants us to do, even if they are informed as best as we possibly can. It is, at times, incredibly frustrating, but this is the nature of our industry. Until next time, I hope that this case study has motivated those reading it to place one’s frustrations to the back of one’s mind. We can’t fix everything, including customers.