PMM’s petrol-powered private investigator, Ben Johnson, steps out of the shadows to solve the mysterious case of the battery who died a hundred times.

When a 2006 BMW 650i Coupe shows up with a dead battery, it’s rarely just a case of the flat battery blues. Especially not when it’s been shipped halfway across the world from America. No one battles the mighty Atlantic over an empty juice box. But of all the BMW specialists, in all the towns, this one had to roll into mine. Its owner sheepishly explained: “It keeps going flat overnight”.

Of course it does.

As with every modern BMW, the first step was to pull the fault codes – and that means all of them. And what did I find among that numerical line up? The usual suspects of course. No CAN bus faults anywhere, but I did find multiple faults on the MOST bus, pointing to a communication failure. I was determined to make this four-wheeled renegade talk.

Then, I ran BMW’s energy diagnosis routine, which narrowed it down to two suspects:

- The CAS (Car Access System)

- The instrument cluster.

That gave me the shortlist.

With no time to waste, I went straight on to the diagnostics. The entire MOST bus (that’s BMW’s Media Oriented Systems Transport) was stone cold. Dead. No comms from anything. The CCC (Car Communication Computer), the master unit for the network, wasn’t responding at all. The fault codes that mention ring break or other issues related to this system usually refer not to a physical fibre optic cable breakage but rather a dead unit and in this case it was the CCC (Fig.2).

But there was already a glaring clue staring me in the face this whole time: The gear stick light – still glowing away, even after locking the car. A breakthrough.

That’s the classic BMW tell-tale. When the CAS won’t sleep, the gear selector light stays on and so does your battery drain.

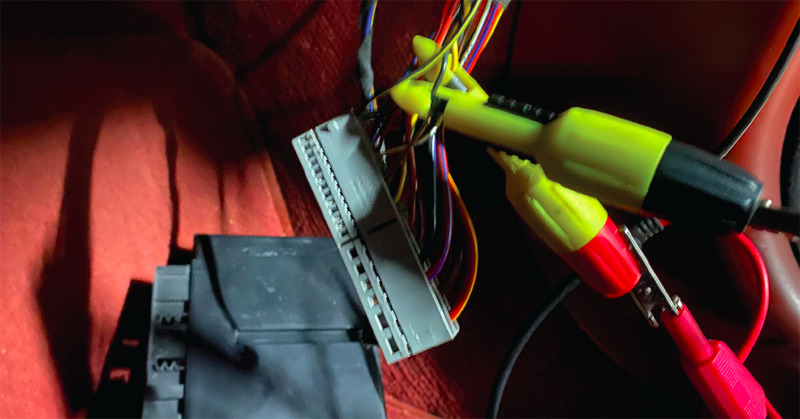

Before even thinking about pulling fuses, I grabbed the oscilloscope. I tapped into the K-CAN (body network) lines right at the CAS module itself (Fig.3). Everything looked above board. The bus would wake when I unlocked the car, then go as quiet as the Finnish forests in winter again about a minute after locking it (Fig.5).

Just to be absolutely sure, I repeated the test. I locked and unlocked the car two or three more times over the next 40 minutes, watching carefully. Every time, the K-CAN went back to sleep exactly as it should. I could now rule out any network chatter or rogue modules keeping the car awake.

So this wasn’t a CAN fault, after all.

Braking bad?

Having ruled out the network, I turned my attention to the brake pedal switch – a known CAS troublemaker on these cars. You see, on BMWs, the brake switch is a halleffect sensor. If it fails, it can keep the CAS permanently awake. I checked it. No faults. No current through the brake circuit holding anything awake. The problem wasn’t external to the CAS. I knew by now that the fault had to be within the CAS itself.

With the network and brake switch cleared, it was time to get physical. I poured myself a hot cup of joe and set to work. I went round to the boot – not to climb inside like a contortionist, but to get the amp clamp on the battery’s negative cable. I latched the boot over (so the car thought it was shut), left the lid slightly open, clipped on the clamp, and walked away, coffee in hand and, perhaps, a Danish pastry in the other. Now, we play the waiting game.

For two solid hours, it sat there pulling 1.6 amps. Every time I wandered back over, same story. After two hours of watching it sit at 1.6 amps, it was time to dig into the front fuse box.

First, I traced the feeds from the battery. Rear fuse box: dead. Front fuse box? That’s where the action was.

I started doing proper voltage drop testing across the fuses. Two stood out immediately:

- The CCC, pulling 1.3 amps through a regular blade fuse.

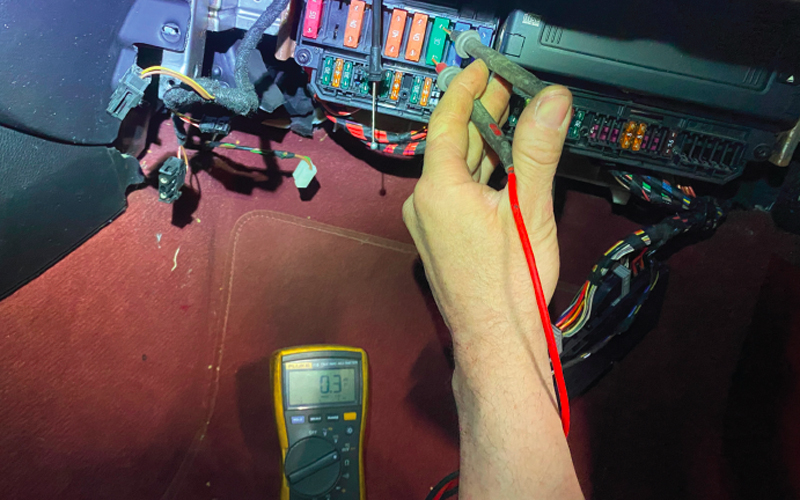

- The CAS, fed by a monster 30-amp maxi fuse: one of those industrial-looking brutes you need to pull with intent was drawing 0.3 amps (Fig.7).

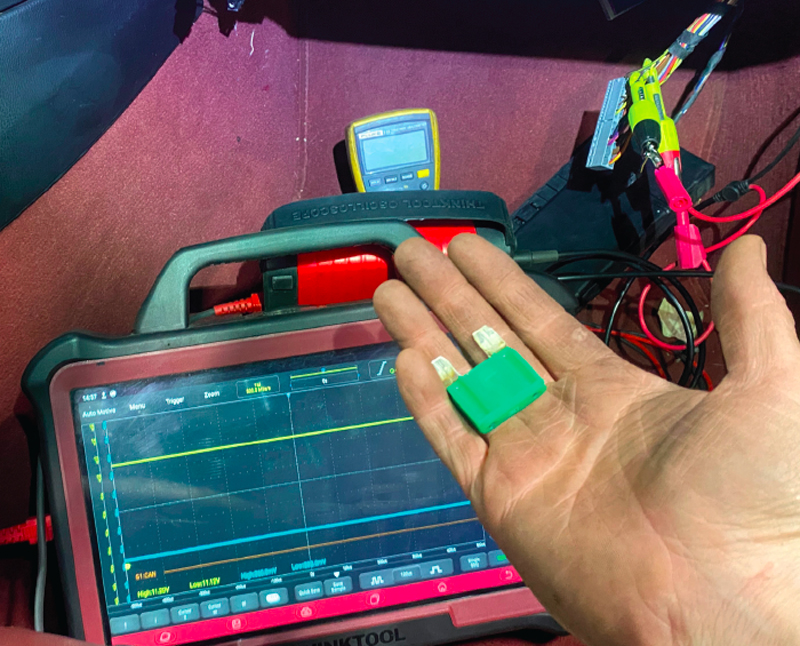

I didn’t just rip them out straight away, though. I scoped, checked, and verified which circuits were drawing current. Then, finally, I pulled both fuses.

Blowing the case wide open

The instant I removed both fuses, the current dropped like a stone. Straight down to 0.050-0.060 amps (Fig.8). At last, the car was asleep.

Once I’d isolated those two circuits, I wasn’t taking any chances. I left the fuses out overnight to make sure nothing else was lurking. When I returned in the morning it was still pulling a textbook 50 to 60 milliamps. Job done.

Next, I stripped the CAS module down and back-probed every single pin. Everything external checked out, including the brake switch again. The only thing drawing current was the CAS itself. Internally faulty.

To be absolutely sure, I swapped in a used CAS unit from another car. Obviously, it wouldn’t start – wrong VIN, no key sync – but that didn’t matter. What mattered was whether the car would sleep. It did. Like a baby in its mother’s arms. No drain. Gear stick light off. Clamp reading stable. It was almost enough to bring a tear to this grizzled diagnostic detective’s eye.

But I wasn’t finished yet. I needed proof, beyond doubt that the old CAS was dead inside. I ordered a brand-new CAS unit, coded it in, programmed it properly. As predicted, it worked. The car went to sleep perfectly, with no more drain.

The CCC went off to Latvia for a refurb, came back fully working, and slotted back into place. MOST bus back online.

The sorry tale I am relating to you revolved around a rare case of double-drain. Double the drain, double the trouble:

1. The CCC pulling over an amp.

2. The CAS silently draining the rest.

Either one would flatten the battery. Together, it didn’t stand a chance.

So how did I uncover the deceptive duo? Through luck? Think again. This wasn’t luck. No miracle software update. No wild guesses. Just patience, proper testing and some solid coffee-fuelled troubleshooting.

Jobs like this remind me that not everything is a coding issue or a software glitch. Sometimes, hardware just fails. But failure isn’t final – not for cars or people.

And sometimes, the best tools are a meter, a scope, a Danish pastry and a bit of good old-fashioned stubbornness.

Coming to the end? I’m only getting started!

If you ever find yourself knee-deep in the electrifying hellhole that is a battery drain – you know the type, the one that laughs darkly in the face of your multimeter, mocks your wiring diagrams and drains not just the car’s battery but your very will to live… here’s my advice: do what I do. Push it. Yes, physically shove it into the darkest, most cobweb-ridden corner of the workshop. Throw a dust sheet over it if you’re feeling fancy. Tell the customer, calmly, with the serene confidence of a Buddhist monk, that it’ll definitely be ready in “about a month.”

Then, and here’s the important bit, get straight back to the quick jobs. You know, brake pads, oil changes, wiper blades. The sort of work that actually pays.

Because, let’s face it, most customers haven’t got the faintest idea how complex fault finding actually is. They think it’s just “plug it in, mate.” Plug it in!? Oh yes, because clearly that £9.99 eBay OBD dongle is going to solve a parasitic drain that’s been festering in the depths of the car for three years!

And managers? Don’t even start me on them. They’re worse. They’re the sort who stand there, hands on hips, asking why you’re not “just fixing it.” As if you’re purposely dragging it out to practice your yoga breathing over the wiring diagram.

No, they don’t get it. They’ll never get it. And do you know why? Because thinking doesn’t show up on the bloody time clock. Now, where did I leave that Danish?