Like any good garage, we start all of our diagnostic jobs with a customer interrogation to try and get a full picture of their complaint. The customer in this case was quite clear that his van had no power whilst driving and that it would not rev above approximately 2,500rpm.

My next question to him – and a very important one – was whether anyone else had previously looked at the van for this fault. Unsurprisingly his answer was ‘yes’, with the garage in question performing a diagnosis before replacing the boost pressure sensor; an overall cost of £85 to the customer, yet no rectification of the problem. After working out his budget I told the customer to leave the van with me so that I could get to work on trying to sort the problem.

After working out his budget I told the customer to leave the van with me so that I could get to work on trying to sort the problem.

Diagnosing the fault

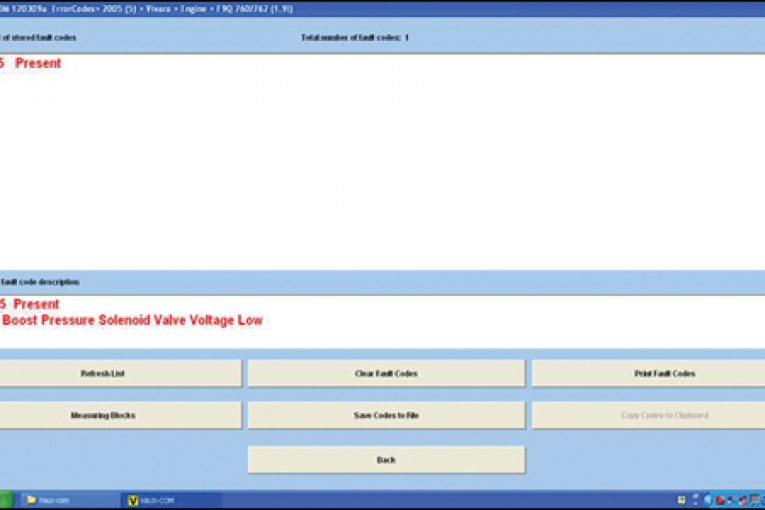

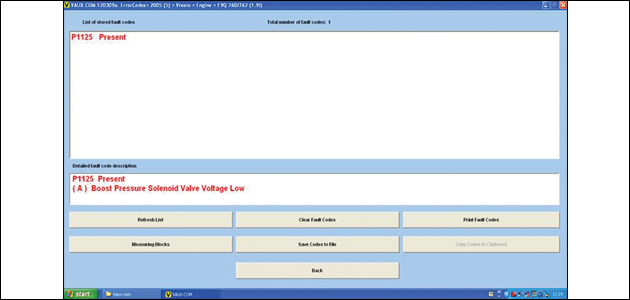

I started my process by ensuring that I could make the fault occur. Sure enough I started the vehicle and on my first push of the throttle pedal the engine would hardly rev at all while the MIL (malfunction indicator lamp) immediately illuminated. I then performed a scan of the engine ECU to retrieve any fault codes (pictured below).

My immediate thought was that I couldn’t believe the garage had changed the boost pressure sensor purely based on this fault code. With no prior experience of this particular fault code I decided that I now had two options:

a) Look at the duty cycle for the boost pressure solenoid valve in the measuring blocks within the scan tool;

b) Scope the solenoid.

I decided to go for the second option due to the fact that it was highly likely I’d have to undertake this task anyway, so I might as well do it now.

As part of my diagnostic process, before I scope or test anything I always try to picture the system and its design in my head. In the system I was about to scope the solenoid has two wires – one of which is NBV (nominal battery voltage) and the other is a PWM (pulse width modulated) signal from the ECU to control the solenoid.

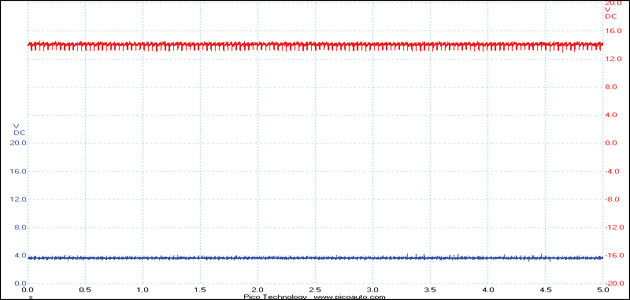

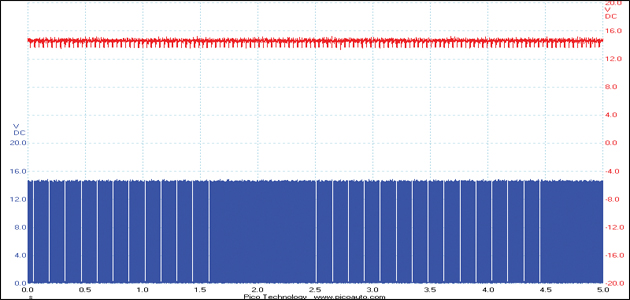

The image below shows the first capture when I attached my trusty Pico using 2 channels – one for each wire (please note that the blue channel is supposed to be my PWM signal and my red channel is my NBV).

As you can see from the capture we had no PWM signal on the blue trace, highlighting that there was no control of boost pressure. In my opinion we had now narrowed this down to three possible faults:

1. The solenoid was internally shorted;

2. The wire between the ECU and solenoid was shorted;

3. The ECU was faulty.

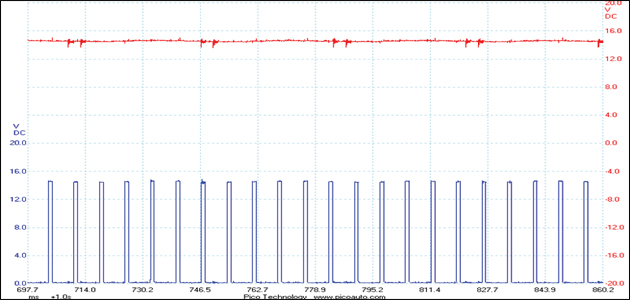

To prove a point I now decided to replace the solenoid with a 501 bulb and scope the wires again to see if we now had a PWM signal.

If you take a look at the scope images with the bulb replacing the solenoid (Fig 3) you can see a big difference (Fig 4 is a zoomed view of Fig 3, so you can see the PWM signal more clearly).

Fig 3

Fig 4

What does this prove?

My investigation showed that we could now be 100% confident of replacing the boost pressure control solenoid, safe in the knowledge that the ECU and the wiring to the solenoid were perfect.

After the solenoid was replaced and fault codes cleared I road tested the vehicle and all was well. The total bill to the customer was £50 for diagnosis/repair (this is our initial diagnostic charge, even though the customer had authorised £150 labour as his budget) and £48 for the solenoid – so not much more than he was charged for the repair that didn’t fix the vehicle!

As an extra bonus, as well as fixing the van I’m now confident I have a new customer for servicing and repairs as he was very impressed with our work and customer care.

You never stop learning

To summarise, this job took me about 15 minutes to diagnose the faulty solenoid and all I required was a little bit of understanding of the circuit design and system operation.

Some of you may ask why I chose this particular job to write up as it’s such a basic fault which is straightforward to diagnose. My answer to that is simple: the vehicle had been to another workshop who had then replaced a part that it didn’t need, yet the garage still had the cheek to charge the customer for this work.

In reality the tests I carried out were very easy and not at all in-depth, proving that you can buy as many fancy scan tools as you like but if you don’t have good training then you’re going to make costly, unnecessary mistakes.