Will our herculean problem-solver Ben Johnson ever reach the Elysium of original equipment and willing customers? First, he must undergo the twelve labours of penny-pinching customers, aftermarket parts and rectifying dodgy repair jobs.

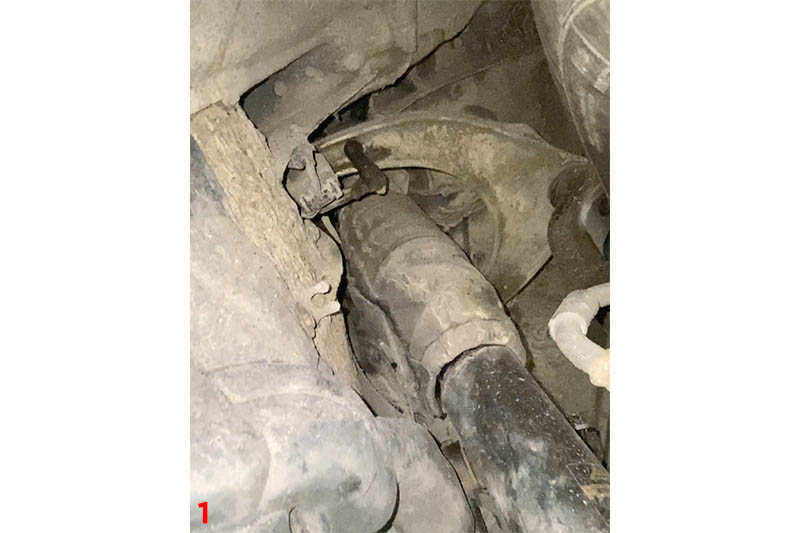

There’s a certain tragic charm to a BMW F11 that’s seen better days. A luxury estate car once built to glide effortlessly down the autobahn, now limping between repeated MOT failures and plagued by questionable fixes. This one, in particular, was a peach. The owner, strapped for cash (whenever are they with cash?) and perhaps common sense, decided that genuine parts were an extravagance he could do without. Enter the fabulously exotic BC Racing coilovers on the front and, wait for it… the original, not so fresh, EDC dampers left on the rear. What could possibly go wrong? (Fig.1/main image).

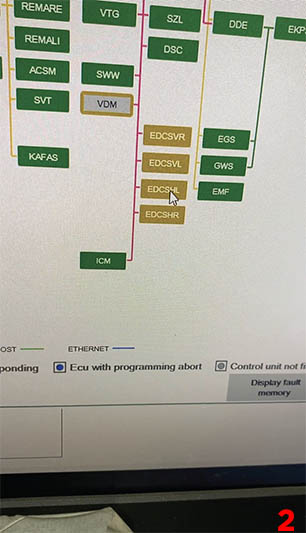

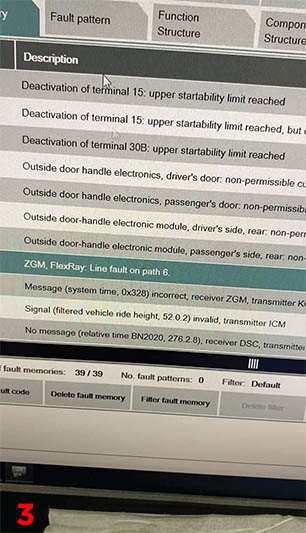

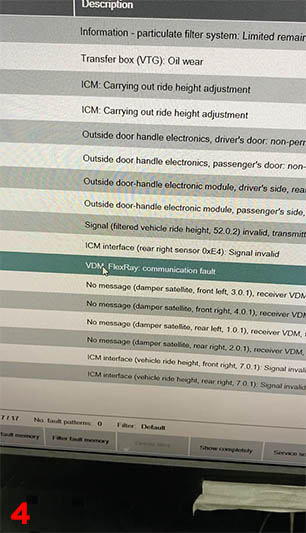

Now, I don’t know if it was out of a fit of desperation or sheer optimism that led to this Frankenstein’s monster of a suspension setup. Perhaps he imagined the car would self-correct like some sort of automotive miracle. Spoiler alert: it didn’t. What he got instead was a suspension system more confused than a cat at a dog show, and behaving equally as inappropriately (Figs.2,3,4).

As if that wasn’t enough, the air suspension had its own peculiar set of grievances, largely due to bent height sensor brackets. (Fig.5) But the pièce de résistance? The electronic damper control (EDC) system was still trying to do its job, despite half the hardware having been lobbed in the bin. And it’s exactly this type of debacle that will inevitably end up on my ramp on a Monday morning, accompanied by a list as long as your arm – which, to be honest, I rarely read. The customer, of course, bemusedly blames this chop-suey kitchen disaster on the poor ICM module: “It must be a faulty ICM module.” Oh, must it? Because if they say so – sorry, I mean if their trusted BMW specialist says so – it must be true. I often half expect these customers to have taken a wrong turn and wound-up time-traveling back to 1983, starring as unwitting contestants on the Jeremy Beadle show. What an abomination this was. If Jeremy Beadle had indeed have jumped out with his cheeky grin, dressed as an MOT inspector, it might have been funny – almost charming, even. But alas, those days of light-hearted pranks are long gone. Instead, what you get now is the reality of good old Ben Johnson, rolling up his sleeves to fix your tragic attempt at reverse engineering.

The second time around…

At some point, as you already are aware, our hapless hero had taken the car to a so-called BMW specialist. Now, I use the term “specialist” in the loosest sense. They’re the kind of people who think coding means pressing a few buttons until the warning lights go out. And that’s precisely what they did – they tried to code out the EDC system. Sort of.

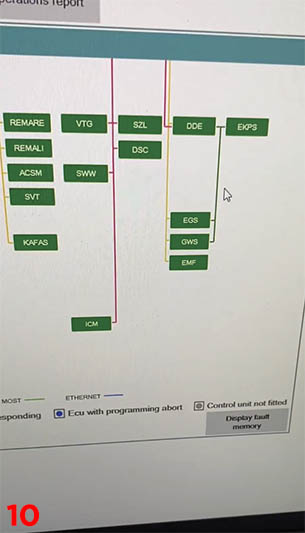

In their infinite wisdom, they managed to deactivate the VDM but left FlexRay port 6 wide open on the gateway module. It’s a bit like locking your front door but leaving the back door open with a neon sign saying, “Help yourself.” As a result, the ISTA tester still showed all four suspension satellite dampers as yellow modules in the vehicle tree – clearly not communicating.

This is where I came in. First, I had to clean up the coding mess. I deleted the VDM module from the car completely, along with all four suspension satellite dampers, by properly closing FlexRay port 6 on the gateway module. But I didn’t just rely on guesswork. I double-checked the vehicle order (VO) to make sure that the EDC and VDM options were fully deleted from the car’s configuration. Finally, the two fuses powering the VDM must be removed. We need to put this system to rest in the most dramatic fashion possible – think EastEnders villain, sudden twist, and an unceremonious exit into oblivion.

Without that step, you’re just asking for trouble. Cars like this don’t take kindly to half-baked coding jobs. Proper coding means telling the car exactly what hardware is installed – and what isn’t. Skip that step, and you’ll be left chasing ghost faults forever.

Before I could begin writing the ride height into our supposedly condemned and utterly broken ICM – which, for the record, was far from broken – I noticed the familiar ham-fisted handiwork on the rear height sensor connectors and bent sensor brackets. (Fig.6) Add to that the moisture seeping into the knackered connectors, and it became abundantly clear: I should probably quit my job as a BMW fault-finder. I will never possess the finesse, nor the sheer bloody-minded determination, to either a) misdiagnose something so catastrophically, or b) break, bend, or condemn nearly every working component on what was once a regal full spec F11.

After bending the brackets back into shape – scrapheap challenge style – with a bench vice, I reattached the now significantly straighter brackets to the rear of the car. I then proceeded to set the ride height, which, miraculously, went through without a hitch.

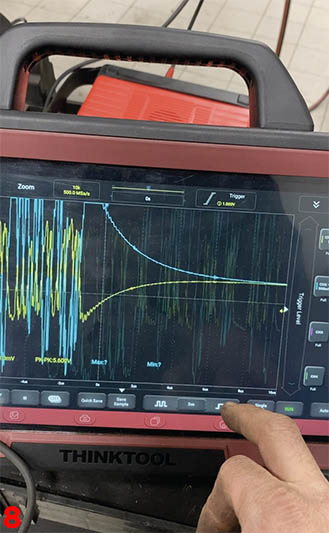

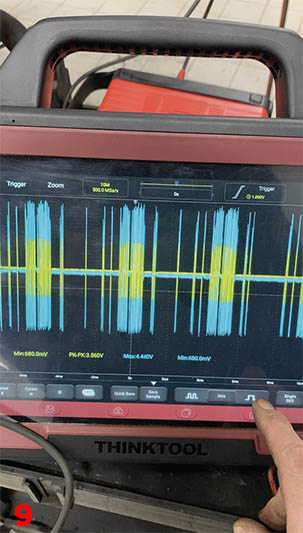

Just to prove how the system should work, for the young lads in the workshop, I added a little twist to the job. I grabbed a 100-ohm resistor (Fig.7) and bridged the front right suspension leg harness connector to trick the system into thinking the damper was still there. Lo and behold, the VDM sprang to life. It was a quick way to demonstrate how FlexRay communication works – and a reminder that even modern cars can be fooled with some clever 50p resistors in place of 2 grand suspension struts. (Fig.8 Flexray not working/ Fig.9 Flexray working)

The final task was to close off the unnecessary FlexRay port 6 connection leading to the right-side dampers using some special software that shall remain anonymous though the readers likely know full well what software I used for this task. Naturally, I closed the left side port as well. Now, what our friend ‘Bodger Bill’ – the self-proclaimed BMW specialist – had done was simply delete the VDM module and satellite damper options from the Vehicle Order (VO). But, and it’s a big but, they hadn’t bothered to properly close the corresponding ports in the gateway module. This meant that every time the vehicle test was run, five ghost components popped up on the diagnostic tree like unwanted party guests. Sloppy work at best – amateurish and untidy in every sense of the word.

With the FlexRay reinitialised and the system properly configured, the F11 was back to behaving like a BMW should and the EDC? Gone forever along with the VDM. (Fig.10) The moral of the story? There’s no substitute for doing things properly. Cutting corners might save a few quid in the short term, but it’s a false economy. Or, as I like to put it, “Buy cheap, buy twice.”

So, next time you’re tempted by a bargain fix or a “specialist” who claims they can sort your car for half the price, remember this: BMWs aren’t just cars; they’re rolling computers. And just like your laptop, you wouldn’t trust a bloke down the pub to reprogram your BIOS. Well, at least I hope you wouldn’t. Until next time, keep learning and keep up the standards!