HEVRA’s Pete Melville explains how component-level repair on EVs may open up a new revenue opportunity for garages. Here, he takes a look at a problematic Peugeot Ion.

When I started on the road to make EV servicing and repairs easier for drivers and for garages, I didn’t know exactly where it would lead. Of course, listing on the HEVRA website makes it easier for a garage to be found, and generates new enquiries; and the support we give to garages gives both the garage and the customer more confidence. But these were all part of the plan. My background has always been in fault diagnosis, and correct diagnosis is of course vital to making a repair cost-effective for the customer and profitable for the garage, especially when parts’ prices are high and lead times are long.

One unexpected avenue has been our involvement in component-level repairs. When a part is particularly expensive, and takes a long time to get hold of, and in many cases is locked to a particular VIN, this opens new opportunities for the garage. Most electronic components can be obtained easily and quickly for just a few pounds (or even pence), and can save the customer thousands. It can often take longer to replace a small component than the whole assembly, but the cost saving justifies a fitting charge that can be profitable for the garage. The garage sells more labour time, the car is back on the road, and the customer saves money too. There’s also a sustainability benefit to repairing rather than replacing.

This being said, the tricky part is often working out which component has failed. However, as part of a community like HEVRA, we’re happy to put time into tracking it down, as the same fault often comes up again and again, and we can all learn from it. Here’s an example of one of these component-level repairs completed earlier this year, and one we’ve seen across the network a few times since.

The Peugeot Ion and Citroën C-Zero are both rebadged versions of the little Mitsubishi i-MiEV. This 2012 example did start and drive, but would sometimes go into limp home mode, and would often stop charging after only a few minutes; and in both cases, this would turn on the EV system warning light.

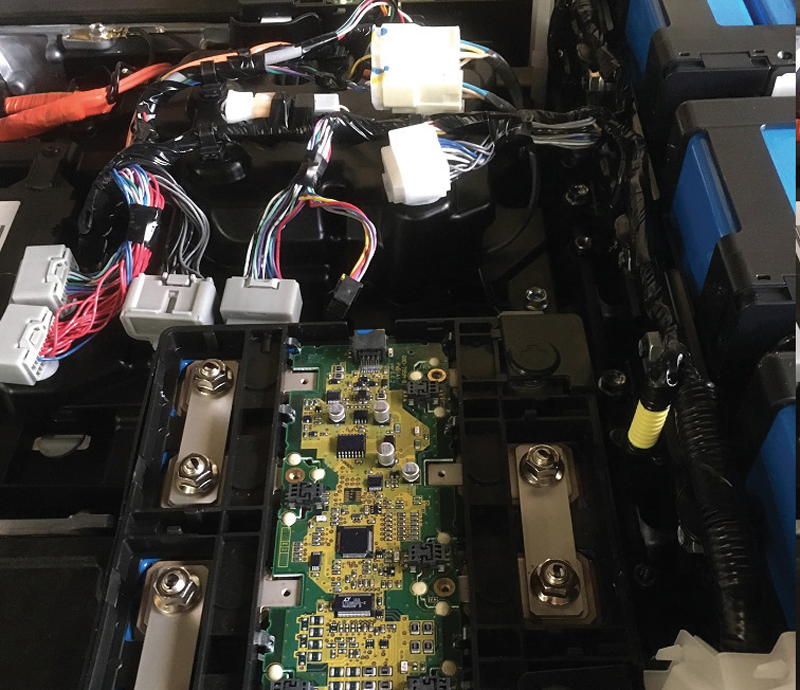

A quick fault code read revealed a fault with the voltage measurement of one of the cells in the battery pack. This car has a central battery ECU, and 12 cell monitoring units (CMU) that each measure the voltage and temperature of either four or eight cells, and report this information back to the battery ECU via the BAT-CAN network. The communication with each CMU was fine, but number six showed some unusual voltage readings, with the voltage bouncing from 3.5 to 0.8V.

‘Back to the drawing board’

So, was it the CMU itself, the wiring, or the cell? Well, it couldn’t be the cell – it is impossible for a cell to charge and discharge like this. The reading shows a perfect reading one minute, and then a ridiculously low reading, suggesting a connection that is intermittent. So, perhaps it’s a wiring fault. Well, actually, there isn’t any wiring to speak of – the CMU is bolted to the top of the cells that it measures, with the circuit board in direct contact with the cells. If the wiring between the CMU and the battery ECU was at fault, we would have no CAN communication. Therefore, it must be a fault within the CMU. Better get one ordered.

This is where a problem arose – the CMU is not available, and neither are any parts within the battery pack, you can only order the entire pack. I didn’t bother enquiring about the price and instead decided to try and source a used CMU (which would then need programming to tell it where it is positioned in the pack). However, these were not available either – these cars are not hugely popular and the only ones I could find for breaking up were quite keen to keep the valuable battery pack as one unit.

This meant it was back to the drawing board with the CMU. I brought the unit back to the HEVRA ‘lab’, and analysed the circuit board under a magnifier, working out which chip performed each function and carrying out multimeter tests to narrow down the problem. We were able to trace the fault down to an individual integrated circuit, which, although not available from Peugeot or Mitsubishi, could be sourced from an electronic component supplier.

The chip is perhaps the size of the nail on your little finger and has 44 legs, so it’s fair to say removing and refitting this little chap is best left to someone who has experience with such things – I gave the job to a local electronics repairer.

Once reassembled and tested, the car could go back to the customer, and with the customer over 100 miles away, the long drive and en route rapid charge was an ideal test to prove the successful repair.