Have you noticed that the steering wheel is misaligned when driving in a straight line? If your answer is yes, this could be a classic symptom of steering geometry issues. Autodata takes us through a few steering geometry essentials to help you in your service, maintenance and diagnostic work.

Steering geometry problems generally tend to occur with the ageing and wearing of components. Nevertheless, they can also be caused by impacting potholes, driving over kerbs, and after a vehicle is involved in a major impact.

Steering geometry, also known as wheel alignment, is the procedure required to check, and if necessary, adjust settings when they have deviated away from the manufacturers’ specifications. However, it is also important to bear in mind that if after a steering geometry inspection there is cause for re-alignment, not all geometry values are adjustable; whenever noticeable deviations from pre-defined settings are observed, the only remedial procedure available could well be component replacement.

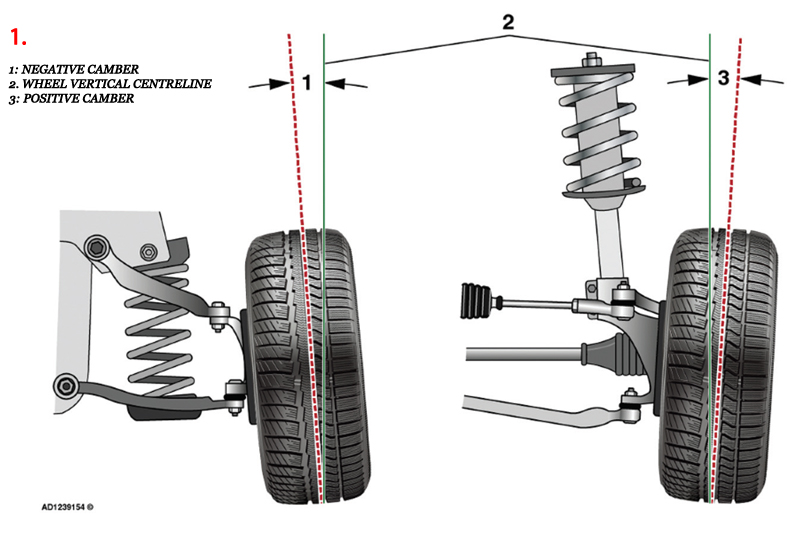

Camber angle

The camber angle (Fig 1/main image) is the direction that the front wheel is leaning relative to the wheel’s vertical centreline. Depending on the lean, the camber angle is either positive or negative. Observe from the front of the vehicle – if the top of the wheel is leaning towards the engine, this is considered negative camber. Conversely, if the top of the wheel is leaning outwards, this indicates positive camber.

If during a steering geometry examination the measurements are outside of specified tolerances, and if the camber angle needs amending, look for evidence of elongated holes on the suspension strut tower. Also look at eccentric bolts or washers securing the upper and lower control arms as a means of adjustment. In their absence, inspection of the suspension and steering components is essential to check for any potential damage.

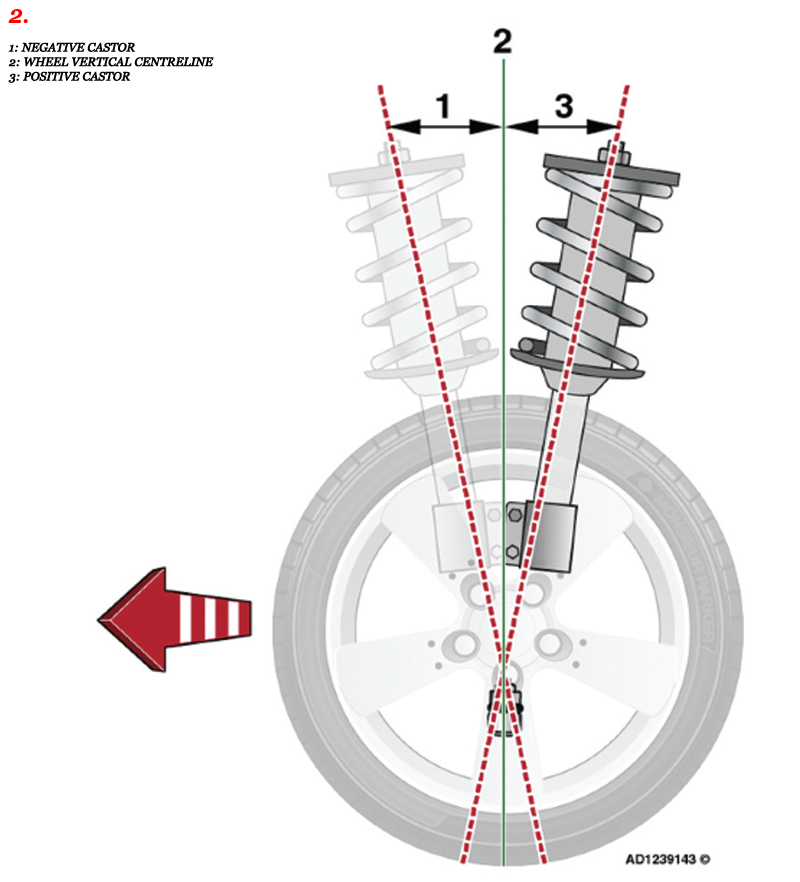

Castor angle

The castor angle (Fig 2) refers to the positioning of the steering axis centreline from the wheel vertical centreline, when viewed from the side of the vehicle.

If the steering axis centreline contacts the road surface ahead of the wheel’s vertical centreline, this is said to be positive castor. Negative castor indicates that the steering axis centreline contacts the road surface behind the wheel’s vertical centreline.

Most modern vehicles are designed with positive castor, which, in conjunction with the other geometry angles, reduces steering effort and allows the front wheels to self-straighten after a bend is negotiated.

Yet, to stop the vehicle from wandering towards the kerbside, the average vehicle castor and camber angles can sometimes be set at slightly opposed settings from left to right, depending on which side of the road the vehicle is driven.

In most contemporary vehicles the castor angle is non-adjustable; nonetheless, aftermarket kits do exist that can be tailored to the suspension to permit castor angle alteration.

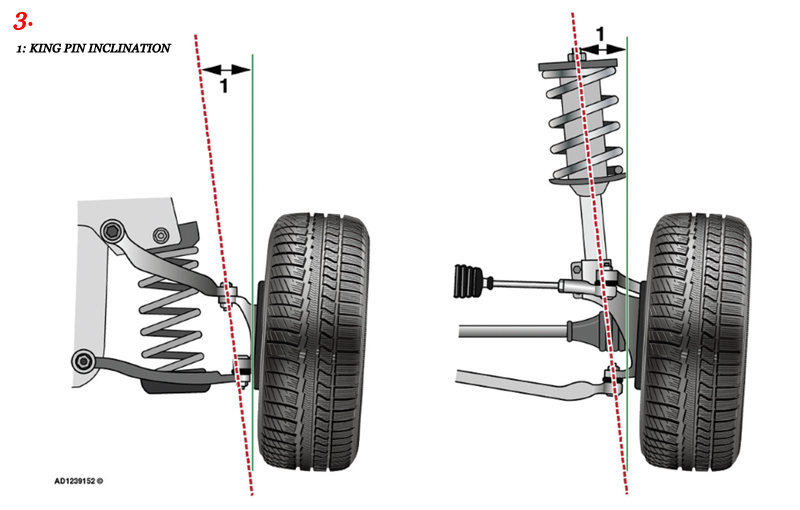

King pin inclination (KPI)

King pin inclination (KPI) (Fig 3), also called steering axle inclination (SAI), is achieved differently, depending on the suspension arrangement. Typically, with the MacPherson strut type suspension, KPI is attained by leaning the strut. While with the control arm type suspension, the angle of the upper and lower swivel joint pivots is offset.

KPI being non-adjustable can often result in it being left unchecked or overlooked in collision situations. Incorrect KPI caused by worn or damaged suspension components usually results in accelerated tyre wear, along with poor directional stability and increased steering effort, particularly when the vehicle is implementing a parking manoeuvre.

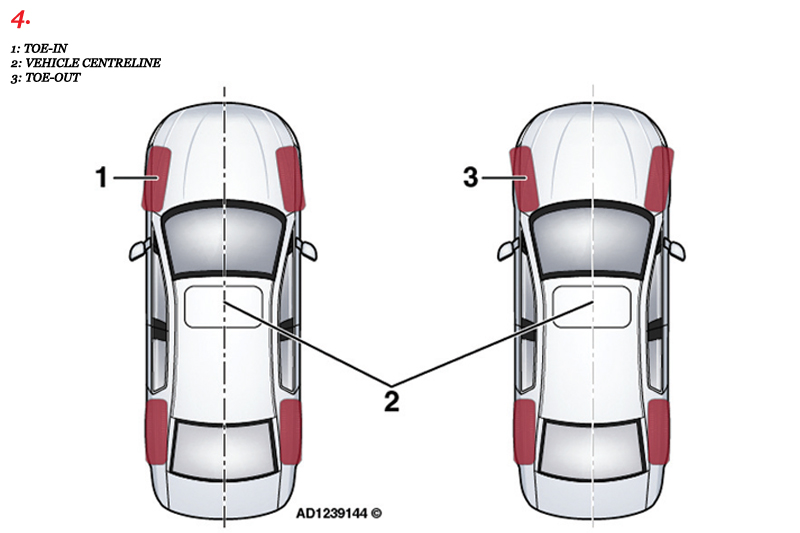

Toe-in and toe-out

Toe-in and toe-out (Fig 4), commonly referred to as ‘tracking’, is the most frequent steering geometry adjustment undertaken. It is the degree to which the leading edge of the front wheels steer out or in from the vehicle centreline, when observed from the front.

Toe-in is when wheels are pointing in towards the vehicle centreline, and toe-out is when the wheels point away from the vehicle centreline.

Making sure that the vehicle’s toe-in or toe-out measurement is correct offers many advantages such as improved straight-line stability, better road handling characteristics, and a more effective steering response.

This adjustment will also allow minor tweaks to correct suspension bush disparities caused by production or accepted wear levels. If adjustment is needed, it is worth remembering to adjust the track rods equally.

Guaranteeing precise steering geometry alignment is vital to prolong the life of tyres and ensure vehicle stability. Regular steering geometry checks are advisable and should not just be performed when changing worn tyres, steering, or suspension components. Checks should also be carried out if subframe removal is required to facilitate gearbox or clutch repair work.

Finally, it is worth noting that rear wheel geometry can influence steering stability as well. It is possible to have the front steering geometry angles correctly aligned and still have a vehicle that pulls to one side or displays abnormal tyre wear patterns. In such circumstances, it is imperative that rear wheel geometry is also considered when confronted with a vehicle experiencing unusual tyre wear or stability issues.

Autodata has a dedicated wheel alignment module to further assist technicians with wheel alignment procedures and help provide workshops with an additional revenue stream.

Within the module there is a comprehensive guide which includes information on subjects such as camber angle, ride height, tyres and adjustment procedures together with manufacturer-specific data.