We’re all familiar with turbochargers and what they do, but do we really understand how they work?

Improving efficiency

A turbo is effectively a pump that forces more air into the engine. It improves performance, without the fuel consumption or emissions you’d get from a bigger engine with comparable power output.

The turbo is mounted between the exhaust manifold and downpipe. Exhaust gases drive the turbine, which is connected by a shaft to a compressor that pulls in air and compresses it. As engine revs increase, more exhaust gas passes through the turbine housing, making the turbine wheel rotate faster – up to 6,000 revs per second, or 360,000 rpm.

The hot exhaust gases can reach 950°C, heating the entire turbo, including the air that’s drawn in. Hotter air reduces power, so it’s usually passed through an intercooler to lower the air temperature.

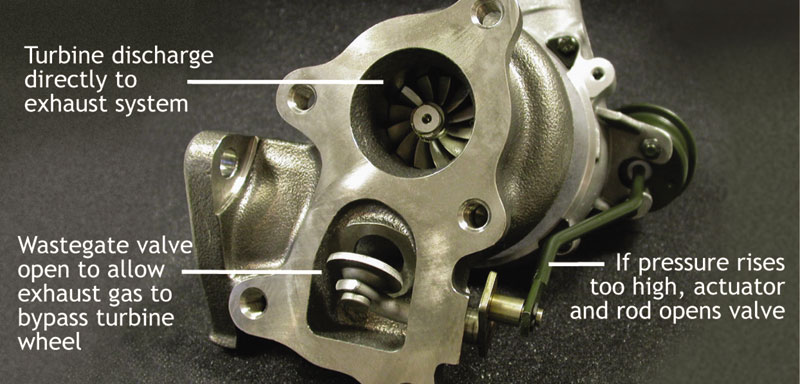

Wastegate turbos

A small turbine gives a good response at low engine speeds, but at higher revs it can overspeed, and overboost the engine. Wastegate turbos are fitted with a valve which allows some exhaust gas to bypass the turbine wheel, preventing excessive boost pressure. This means the turbine wheel can safely be smaller, giving better engine response yet still maintaining maximum power output.

Variable turbine turbos

These turbos move vanes or a nozzle to alter the turbine stage, allowing more efficient use of exhaust gas to provide an optimum boost level across the widest range of engine speeds. This improves response and fuel economy, enhances engine braking and allows vehicle manufacturers to use smaller engine packages to achieve a given power output.

Most variable turbine turbos are electronically controlled by the engine management system, and are highly complex. To be sure of reliability, they’re best replaced with brand new OEM units or BTN Turbo’s range of OMX units, which are remanufactured by the original manufacturers to 100% OE specifications.

The importance of oil

A turbo is built to tolerances of thousandths of a millimetre. At its heart, the shaft bearings float on a thin film of oil, fed under pressure from the engine. The oil is kept in place by unique oil seals, designed to cope with the turbo’s extreme temperatures and pressures, and prevent leaks into the compressor or turbine housings.

Nearly all turbo failures are oil-related – running a turbo without oil for five seconds is as harmful as running an engine without oil for five minutes. So whenever you fit a replacement turbo, make sure it has a correct, clean oil supply.