PMM ’s disgruntled man in Finland gets under the bonnet of a BMW M5 which had been around the houses and under the arches.

Ah, the infuriating encounters we car mechanics endure. A situation so disheartening, it makes one hesitate to even embark on the repair journey. All we desire is to smoothly slide those car keys back to the eagerly waiting customer across the grotty laminated service counter. This, my friends, is what we term in the trade the “butchered” effect.

Picture this: a well-meaning somebody or an establishment parading as a “BMW specialist repair centre” plunges into the challenge with all the sincerity of a saint. Yet, their efforts barely scratch the surface, a mere 20 per cent commitment to a quality repair. Sometimes, one can’t help but feel they should step aside and leave it to the seasoned professionals – perhaps, dare I say, someone like myself?

Now, let’s shift gears to the star of this month’s spectacle – a 2001 M5 flaunting the remarkable S62 V8. This powerhouse, when hitting the right notes, belts out over 400 horsepower, effortlessly delivering that brute force to the tarmac. It’s akin to a Black Widow’s catapult launching a rosebud into Mr. Smith’s unsuspecting living room window, a nostalgic mischief I, in my youth, may have been a tad too familiar with.

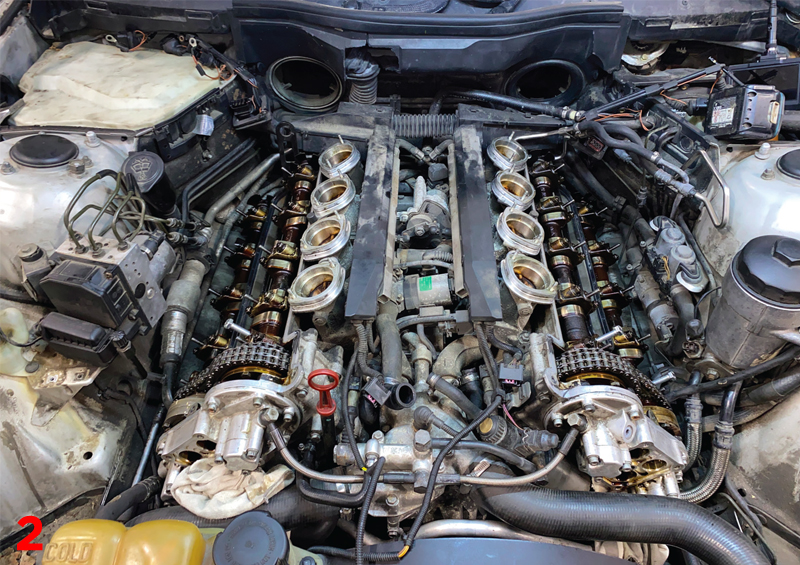

Butchered, a fitting term as our M5 owner poured forth a saga, dedicating over half an hour of partially incoherent babble to unravel the tangled web of what had and had not been attempted. It unfolded as a torrid affair, enough to make a grown man weak at the knees. As I bravely popped the bonnet, a cacophony of wiring harnesses greeted me, their grotesque, aged, hardness akin to arteries in dire need of a triple bypass, making even the toughest carotid seem pliable. A profound sigh escaped my lips; this, my friends, was shaping up to be a colossal pain in the bottom (Fig.1).

When faced with the Herculean task of unveiling the mysteries concealed within the timing covers and dismantling the intricate VANOS system, the first order of business was to decipher the fault codes, and oh boy, were there plenty. The primary culprits included the ominous failure of Bank 2 VANOS in the pressure hold test, hinting at an internal leak – undoubtedly a result of battle-worn piston seals within the VANOS hydraulic units. Additionally, there lurked a perplexing issue on Bank 1 with the exhaust camshaft timing.

Swiftly, a decision was reached to extract the hydraulic units from both Bank 1 and 2, paving the way for the installation of Beisan Systems seals. These little wonders, neatly packed in a convenient pouch, house an array of o-rings and the notorious Teflon seals, infamous for their elusive snug fit onto the sliding pistons. These pistons propel the spiralled VANOS gear, in and out, which takes care of advancing or retarding the camshafts independently of the chain-driven sprockets.

Gaining access

The dismantling journey, akin to moving a mountain of parts, presented its fair share of challenges, with the lower rear securing bolt on the timing covers proving to be a formidable adversary. However, amidst the struggle, a curious revelation unfolded. The Bank 1 exhaust VANOS sprocket looked like it had had a spa day recently – totally different in colour compared to the other three, ancient-looking sprockets that seemed as old as the car itself. Makes you wonder, did they slap in that VANOS sprocket properly? Especially the diaphragm spring inside the heart of the assembly (Fig.2).

Rebuilding a hydraulic unit might sound like a walk in the park, but when it comes to the S62, it’s like navigating a minefield with a fine-tooth comb. The S62 demands the kind of care and attention reserved for delicate surgery, given the myriad ways things can go spectacularly Pete Tong. And, oh boy, in this case the previous butchers had gone fullblown Pete Tong, a fact I discovered when I yanked off the VANOS wheels.

Here’s the kicker – they did a grand job replacing the Bank exhaust 1 sprocket and slapping in a beefier diaphragm spring. Cheers to that! However, after that, they threw caution to the wind and forgot a crucial detail. The intake camshaft was doing a little skip-tomy- lou, thanks to the absence of the newer, more robustly engineered spring diaphragm to the VANOS sprocket. What does that mean? Well, it’s a recipe for disaster. The camshaft decides to play the timing roulette because the spring tension is slacker than it should be, failing to keep it in sync with the sprocket. Basic stuff, yet here we are.

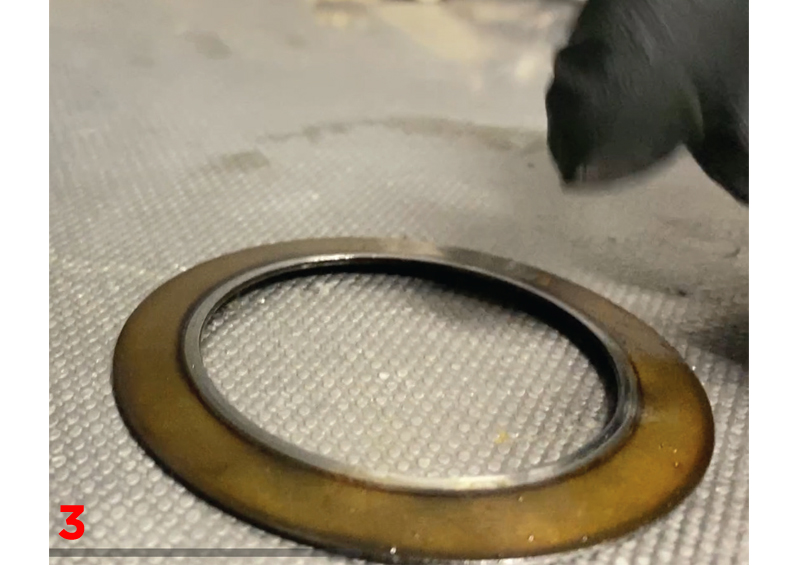

With determination and the thought that I had got this far, I took on the task of replacing all the diaphragm springs, even replacing the exhaust sprocket diaphragm spring on Bank 1, just in case (Fig.3). As I pieced everything together and cranked the engine over four times, a satisfied grin spread across my face. The timing marks aligned with the precision of a military drill. Now, it was time to set my sights on the VANOS hydraulic units.

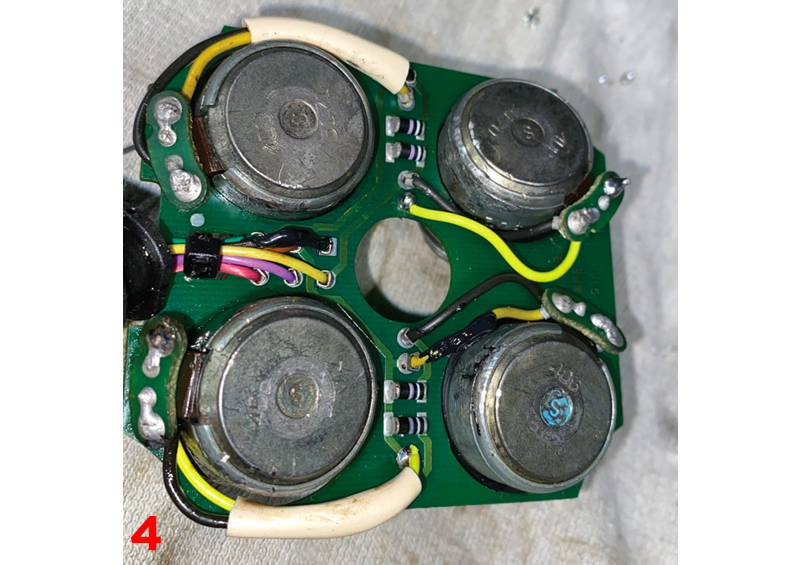

Straight into the battlefield, and what do I spot first? A scene of wiring chaos around the solenoid pack on Bank 1 (Fig.4). Oh yes, the previous contenders had the finesse of a bull in a china shop, damaging the delicate wiring to several solenoids. All this requires the precision of a watchmaker, not that of a demented, screwdriver-wielding chimpanzee.

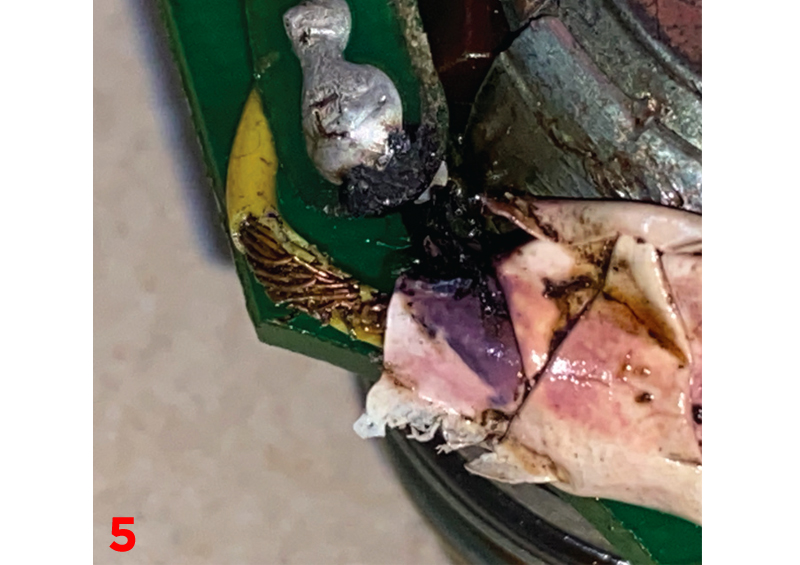

Left with no choice, I rolled up my sleeves, grabbed my soldering iron, and embarked on a mission to de-solder and replace the wreckage they left behind. A reminder that sometimes delicate hands are needed in this line of work (Fig.5).

With the solenoid pack back in action, it was time for an O-ring and Teflon seal finger nail wrecking session. Each piston got its dose of tender loving care as I meticulously ensured a snug fit. Reassembling these components back into the car became a hunt for the sweet spots on the spiralled gears – all four of them. For a more detailed guide on this crucial step, swing by my YouTube channel ( WWW.RDR.LINK/ABI007).

Now, why is this so pivotal, you may wonder? Well, let me spill the beans. Messing up this delicate operation means the VANOS advance and retard sweep go haywire, triggering a fault code that illuminates the E39’s most dreaded light – the MIL. And nobody wants to deal with the MIL; it’s like the car’s way of saying, “you had one job, and you blew it!”.

With everything back in place, all that remained was to fire up this bad boy and take it down the road for a good old thrashing. Well, at least that was the plan until I remembered we’re in Finland – the land of massive speeding fines and downright miserable weather. During this time of year, it meant dealing with god-awful iced-up roads and no way at all to get the power down. Gutted.

Still, I managed to give the old V8 a good run, pushing it up to 6,000 rpm, and boy, did it sound incredible. Back in the workshop, with not a fault code in sight, I parked the old M5 outside overnight. The real test came with a lovely -20°C cold start – a challenge it passed with flying colours (Fig.6).

The customer swung by to pick up the car, and after all this you’d expect sheer bliss and gratitude, right? Well, not really. This owner, like many others, has never picked up so much as an oily rag in his life, let alone a spanner. The intricacies of how VANOS works? Forget it! What did I get for my hard work? The usual moaning about the cost. Sometimes I wonder why we bother at all; but then again, we do get nicer customers, and that makes it all alright… Until next time, keep spannering.