Josh Jones explains why you can’t always rely on the ECU to tell you when something’s wrong. In some instances, there’s nothing better than the human senses.

It was a pretty relaxing festive period for me, with diagnostic dilemma-induced stress at a low level, which was enjoyable and gave me time to get busy with the scope, to further build my waveform library and learn even more in the process.

The main example of this was a job on a 2014 Ford Transit Custom with relatively high mileage on the clock, with just shy of 160,000 miles racked up during its four years on the road.

The van was with me for maintenance that was unrelated to the fault I am about to describe, but once I had jumped in to move it into my workshop I really couldn’t help but notice the way this thing was running. No visual cue of any kind was being displayed to the driver; not even the EML was lit, but the engine was so rough I initially thought it had a dead misfire. The driver had mentioned nothing but when quizzed said that he was aware that it was a bit shaky when ticking over, but that was about it. Investigation was definitely required as I felt that the engine wouldn’t go that much further without potential damage, judging by the way it sounded and felt at the time.

Given the mileage, I thought basic mechanical tests would be needed at first to confirm integrity of the engine itself, so a relative compression test was carried out using an amps probe (I aim to use unobtrusive testing wherever possible, especially where 160,000 mile glow plugs are involved!) and compression looked almost perfectly level across the board. It even sounded fine when cranking with the fuel system deliberately disabled. On road test the engine performed much more smoothly at higher rpms, so again, without wanting to dismantle anything I took from this that the air path into the combustion chambers was OK and inlet tract soot blockage was unlikely to be the culprit. I suspected a fueling accuracy issue.

Although personally I much prefer working on petrol engines when it comes to diagnosing running faults (usually more information on mixture composition is attainable due to closed loop exhaust monitoring being fitted in all cases) I like using live data to view injector correction factor or smooth running control readouts on diesel engines as a starting point if I feel that fueling may not be correct on a specific cylinder, which was the case here.

Even with the engine running like a bag of spanners, the contribution read out as almost balanced across all four cylinders with only minor differences, which surprised me greatly but did perhaps explain why no DTC had been logged in relation to this fault. I may have thought it was running really badly but the engine control unit didn’t seem to have cause for concern at all!

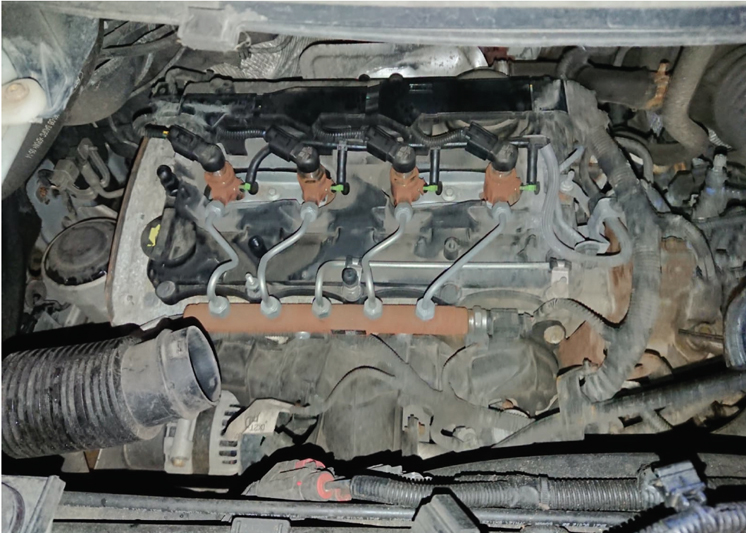

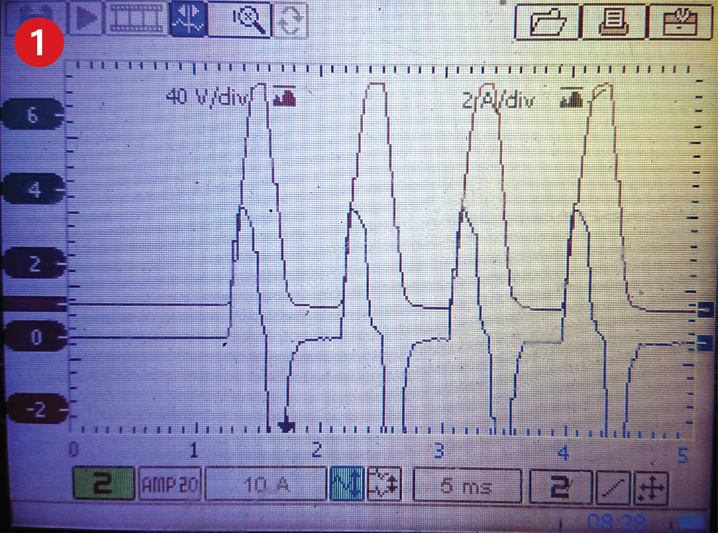

As I was so convinced the problem was cylinder specific but the cylinder balance data seemed inconclusive, I thought I would check injector activation with a scope trace to make sure there was no electrical issue with fuel delivery and to see if I could spot anything of concern. The injectors are solenoid type and I connected to look at activation voltage and checked current flow as well (Fig 1). After taking the same trace from all four injectors, I could see nothing obvious that would point me to the cylinder with poorest performance. The individual injection events were clearly present with equal peak voltages and current flow patterns across all four pots.

I was now fairly certain I was looking at the other end of the injectors as the perpetrator. I doubted that the spray pattern looked that great on any of them after that kind of mileage, but before condemning components that are relatively pricey to replace and as the problem seemed to be more prevalent at lower engine speeds, I wanted to make sure that the intake air composition wasn’t made up of too much exhaust gas. Despite the fact that the EGR valve on this engine is fitted with a position sensor, I always like to confirm directly that the valve isn’t stuck open, as opposed to taking the ECU’s word for it.

The position sensor wire was easy to find at the valve multiplug, and simply running the engine for a short while with a voltage trace being taken was enough to confirm the valve was being moved and could be shut when required. I then carried out a manual cylinder balance test to identify the cylinder causing the most grief, and it turned out to be cylinder 2. I sent the injector to be tested, and purely out of interest I asked for feedback on the amount of wear that had been sustained. It was said that the spray characteristics were pretty shocking and it was not surprising that it was causing an issue. Seeing as all the units were original and had been subjected to the same amount of work, I recommended replacement of them all.

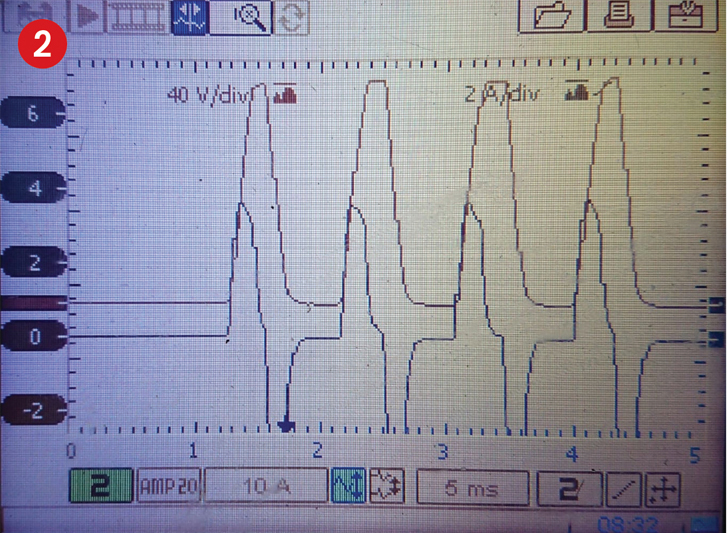

Following their replacement and coding, I took the same trace from the new unit on cylinder 2, just to note any potential differences between the electrical components of a 160k injector versus a new unit (Fig 2). It was clear that the activation components (solenoid etc.) don’t really suffer much during a lifetime of use but the nozzle end had just become so contaminated and worn that it was unable to deliver fuel in the desired fashion, and with the spray pattern being so critical in this type of engine it had a serious effect on smooth running control.

It was interesting that prior to repair, the exhaust from this engine smelled very strongly of partially burnt fuel, even when warm, and no doubt this would have taken its toll on the poor old DPF and engine oil. There was a complete transformation in the way this vehicle drove after repair. If left alone it could well have had expensive consequences for the owner further down the line. The severe injector wear was not enough to trigger a fault code or to really even show up in live data readings, so it needed intervention from good old human senses to initially spot something was wrong, and that I believe is our job as technicians. In this case it would have had to get an awful lot worse before the problem was detected by either the ECU or the driver.